👾 Towards Deep Learning Models Resistant to Adversarial Attacks - A review

Adversarial examples

Let’s start with a simple quiz to see how your vision fares against a neural network.

What is this?

Obviously, this is a gibbon.

If this didn’t make you scratch your head wondering “what kind of skullduggery is this?”, then either you know what is coming up in the next section or you are a bot relying on computer vision.

While the mainstream media are worrying about a distant future run by psychopath bots, this example illustrates a critical limitation current AI systems possess. Nowadays, we hear the terms AI or deep learning thrown into everything from facial recognition to autonomous driving. However, the existence of adversarial examples reminds us how vulnerable such critical systems can become. An adversarial example is an input which has been tampered in a way such that a DNN classifies it incorrectly.

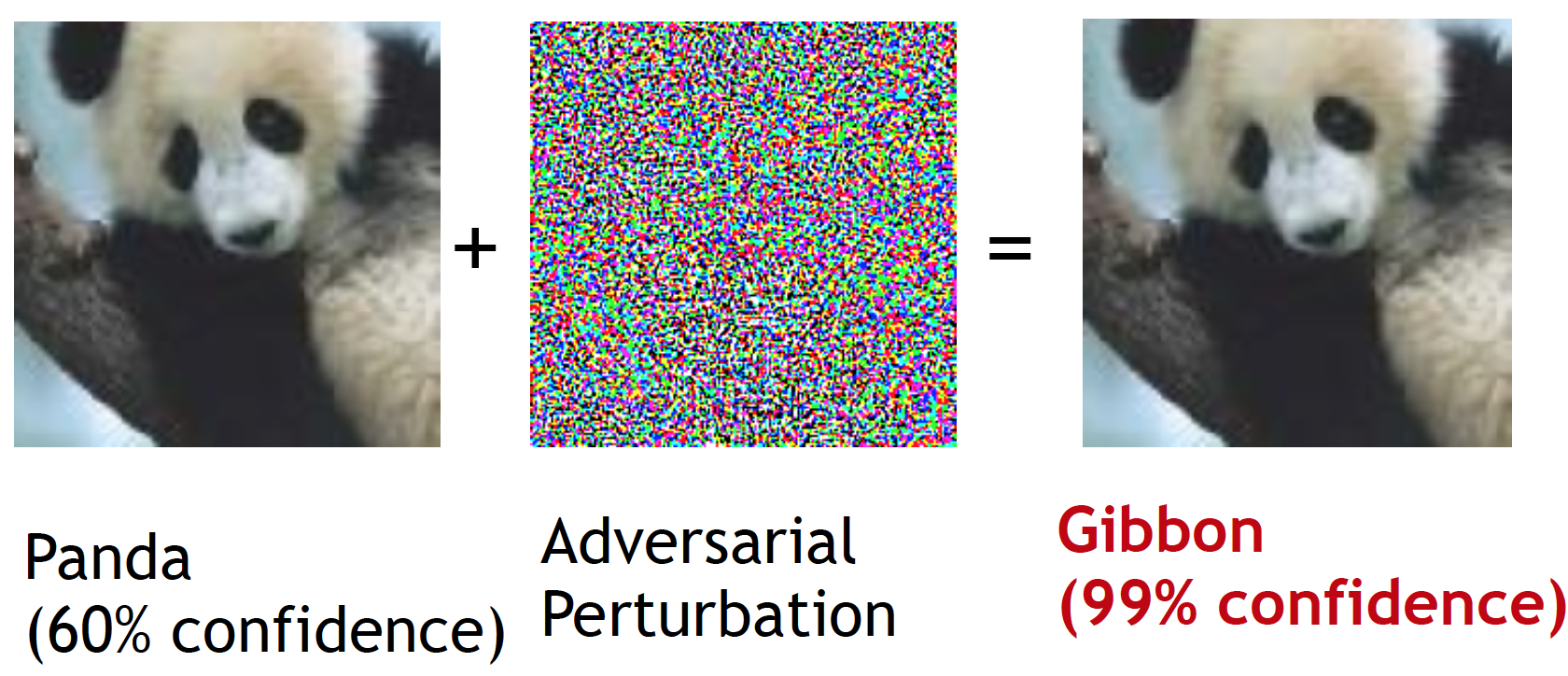

Here we show how the above example is created by adding an adversarial pertubation to an image of panda. Despite no difference is visible to human eye, the DNN confidently classifies the updated image as a ‘gibbon’.

An adversarial example. (Image source: Goodfellow et al.)

An adversarial example. (Image source: Goodfellow et al.)

The excellent blog post by researchers at OpenAI provides a glimpse of real world AI safety issues which can be caused by adversarial attacks.

Generation of adversarial examples

Although there are several ways to create adversarial examples, Fast gradient sign method (FGSM) and its iterative version (BIM) are the most frequently used methods. The FGSM attack creates an adversarial example by adding a small perturbation \( \epsilon \) to an example \( X \), \(X^{adv} = X + \epsilon \cdot sign(\nabla_X J (X, y_{true})).\) The perturbation has \( l_{\infty} \)-norm equivalent to \( \epsilon \) and its direction is computed by the sign of the gradient so adding this pertubation to \( X \) increases the loss \( J \).

Clevehans, the adversarial example library developed by Ian Goodfellow and Nicholas Papernot includes implementation of most of the adversarial attacks and defenses including the paper we are discussing next.

Defenses against adversarial examples

Regularization such as dropout or weight decay makes models robust against overfitting. But they are not effective against the newly discovered phenomenon of adversarial examples.

The two main adversarial defenses are

- Adversarial training: In addition to the real examples, the model is trained with adversarial examples (eg: generated by FGSM). The paper by Kurakin et al., discusses how CNNs can be adversarially trained with ImageNet dataset.

- Defensive distillation: An identical model is trained with output probabilities predicted by another model which was trained on the same dataset. Originally, model distillation is proposed as a technique to compress trained models.

However, these techniques are shown to be vulnerable to more advanced attacks (eg: Basic iterative method (BIM)). Adversarial training using adversarial examples generated by such attacks hasn’t proved to be effective either.

The paper, Towards Deep Learning Models Resistant to Adversarial Attacks reformulates the iterative FGSM attack as a projected gradient descent (PGD) on the negative loss function and shows models trained against this PGD adversary is robust to all first order attacks (uses only the gradient information).

PGD training

This approach leverages the min-max formulation proposed by Lyu et al., 2015 to incorporate adversarial perturbations into the loss function.

A standard classification problem can be expressed as finding parameters \( \theta \) which minimizes a loss function \( L(x, y, \theta) \) (for example, cross-entropy) for a set of examples \( x \) with corresponding labels \( y \). If we assume that the examples are sampled from a distribution \( \mathcal{D} \), the optimization problem reduces to finding parameter \( \theta \) which minimizes the risk \( \mathbb{E}_{x,y \sim \mathcal{D}}[L(x, y, \theta)] \). If we want our classifier to stay robust to an adversary which perturbs an example \( x \) by \( \delta \), the loss function is updated to include this perturbation. \(\min_{\theta}\bigg[\mathbb{E}_{x,y \sim \mathcal{D}}[\underbrace{\max_{\delta \in \mathcal{S}}L(x + \delta, y, \theta)]}_\text{inner maximization}\bigg].\)

The min-max formulation, as evident from its name, consists of a minimization problem and a maximization problem. The inner maximization problem is tasked with adding a perturbation to the input x which achieves a higher loss. On the other hand, the goal of the outer minimization problem is to learn model parameters \( \theta \) minimizing the loss which is being maximized by the inner maximization.

According to this definition, if the adversarial loss of a model is small for all adversarial examples \( x+\delta \), the model should be robust for all allowed adversarial attacks.

How to solve this min-max optimization problem?

This optimization problem is non-convex. Thus, gradient based optimization can not be directly applied. Previous work had to depend on linear approximations of the maximization formulation. For example, Lyu et al., obtained a closed form solution for worst-case \( \delta \) by first approximating the inner maximization problem with Taylor series and then applying Lagrangian multiplier method. This simplifies the optimization problem to minimizing \( L(x+\delta) \), which can be written as a regularization term with Taylor series. For \( l_{\infty} \)-bounded attacks (commonly used type of attacks) this simplified formulation becomes identical to the fast gradient sign (FGSM) attack.

This paper claims that calculating gradient at the maximizer of the inner maximization problem provides a valid descent direction for the saddle point problem. Instead of explicitly maximizing the adversarial loss in the inner step, existing adversarial attack algorithms are employed for maximizing the loss. Particularly, for Experiments the authors use a multi-step variant of the FGSM attack, essentially, prjected gradient descent on the negative loss function. Now the saddle point problem reduces to minimization of the loss, where the loss is calculated for the adversarial examples generated by this adversary. Their attack iteratively applies FGSM attack and afterwards the adversarial example \( (x+\delta) \) is projected to \( (x-\delta, x+\delta) \) range, hence it is named the projected gradient attack (PGD).

The lecture note by Harikrishna Narasimhan is a good introduction to projected gradient descent. (The first two lecture notes in this series set the background for PGD)

The running time of adversarial training with k-step PGD attack is (k+1) times the training time without adversarial attack. Due to this reason their experiments are limited only to MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets.